The European Commission has adopted a proposal to review the current roaming regulation. The proposal is quite conservative, as it extend for further 10 years the current regime of Roam-Like-At-Home (so called “RLAH”): this means that, except for specified exceptions, travellers within the EU continue to be entitled to rely on their domestic tariffs, without the risk of being charged with additional roaming costs. This initiative is politically welcomed since the end of roaming surcharges has been always seen as one of the most visible achievements of the European Union vis-à-vis ordinary people.

The new rules intends also to clarify, inter alia, that travelers should also:

- enjoy the same mobile network quality and speed abroad, as they enjoy at home;

- have better information about the possible additional charges when calling service numbers, such as customer care services, while roaming;

- be aware about alternative means of access to emergency services that are available in the visited country.

Up to this point, all good news. And now let’s look at the dark side. 🙂

A European mobile market does not exist yet

The Commission is prolonging the “RLAH” regime, making it mandatory for further 10 years because there is the risk that, in the absence of ad hoc regulation, roaming prices would likely go up again and European citizens would end back facing surcharges when travelling. The Commission was considering, amongst various options, to lift the RLAH obligation, but at the end they did not do it. Conversely, they concluded that the mobile market forces would have recreated roaming surcharges. Sadly to say it, but this is the reality.

In other words, after 25 years of liberalization and 10 years of specific roaming regulation, the European mobile industry still cannot deliver an ecosystem where mobile operators play on a European level and are incentivized to offer European tariffs, without roaming surcharges. By contrast, they continue to compete at domestic level (even when they are part of multi-country groups) and therefore only offer domestic tariffs which, unless a RLAH obligation applies, would normally increase with roaming surcharges for travelling users. Why that? The issue derives, inter alia, from the contradictory European telecom policy that, on one side advocates for the single market and the end of roaming surcharges, on the other disincentivize mobile operators to play at cross-borders level. This is not so easy to explain, but we will try.

RLAH exists only for users, not for operators.

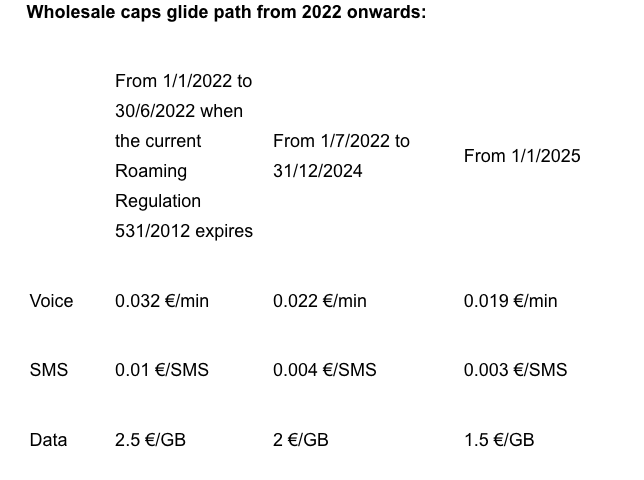

The problem comes from the fact the RLAH regime exists only for consumers, not for operators. In other words, roaming surcharges disappeared for consumers, not for operators. Operators continue to pay the cost of foreign networks for the roaming clients, even when they are obliged to continue to apply domestic tariffs to them in force of the RLAH regime. Should wholesale roaming costs be higher than retail tariffs, then a prolonged roaming service will create non-recoverable costs to mobile operators. This is not so rare, because according to the most common mobile tariffs in the EU one Gigabyte costs, on average, 20 cents for a consumer, while the corresponding roaming wholesale costs can be much more expensive: the Commission is currently capping such wholesale prices at 3 Euro, a cap which should going down only to 1,5 Euro in 2025 and stay so until 2032. Obviously, such caps are disconnected from market reality and cause some operators to incur non-recoverable costs when providing roaming services (non-recoverable because the RLAH regime prohibits to add roaming surcharges and that the instruments provided by the regulation, such as the sustainability remedy, are not realistic).

The competitive consequence of this wholesale roaming costs scenario is that for the majority of mobile operators is not economically viable to let their users to roam abroad systematically, since they would lose money.

The roaming markets is not competitive

The disconnection between wholesale roaming charges and market reality works differently amongst operators. Bigger mobile network operators (“MNOs”) may enjoy much lower wholesale roaming tariffs when negotiating with other mobile operators (normally of similar size), on the basis of bilateral agreements, since they exchange roaming traffic and compensate the costs. However, the victim of this system are small mobile operators (whose traffic is lower than dominant MNOs) and MVNO (mobile virtual network operators) which are unilateral buyers of wholesale international roaming access given that they do not own a radio access network in the countryies where they operate. MVNOs, in particular, cannot host any inbound roaming traffic from an MNO in return for the roaming traffic that the MVNO sends out to that foreign MNO. An MVNO can typically only buy at wholesale level the outbound roaming traffic generated by its customers abroad, without the possibility to trade/exchange (part of) this outbound roaming traffic against inbound roaming traffic. This means that MVNOs cannot offset the costs that the abolition of retail roaming surcharges has generated at wholesale level. Because of the above, MVNOs are in a structurally different situation from MNOs when negotiating wholesale roaming access and thereby have more difficulties in negotiating fair wholesale roaming agreements.

The MNOs tend to protect domestic markets, despite the Single Market

The combination of the above situation, such as the lack of competition in the roaming market, on one side, and the roaming regulation discouraging mobile operators to compete beyond national borders, creates the current scenario: bigger mobile operators are incentivized to protect their domestic market, where can extract oligopolistic profits, while high wholesale roaming charges work as a barrier from foreign mobile operators. An evidence of the above is that even mobile operators which are part of multinational groups continue to compete at national level, despite the fact that they could potentially offer pan-european tariffs in the countures where the group is present.

Considering such a scenario, it is not a surprise that mobile operators tend naturally to impose roaming charges to travellers, unless this is forbidden by way of regulation (as evidenced by the reality). This is a consequence of the fact that their business is domestic-centric, non pan-European.

RLAH is for travellers, not for citizens

As a further consequence of the above, the proposed regulation confirms that RLAH applies only to people who are travelling within the EU, and therefore the benefit is limited for a given duration. If travelers use mobile phones abroad for more than 4 months, then the mobile operators are entitled to cut the RLAH regime and start again to apply roaming surcharges. “Permanent roaming”, that is to say the potential option for a citizen to buy a sim card in a country and use it permanently in other EU countries is not welcomed and it is even considered as a practice to be fought against. This is due to the fact that the Commission does not want to affect the economics of the mobile operators which, as said above, are based on national/domestic patterns. However, by doing so the Commission takes a direct responsibility for the non-achievement of a European mobile market, it is really difficult to blame the market.

PS: Here the proposed glide path for the wholesale roaming caps:

Categories: international roaming

4 replies »