[continuing from the previous post about the link-tax]

Art. 17 (former 13) of the Copyright Directive, concerning the liability of online content-sharing platform and the upload filters, is the most “systemic” part of the European copyright reform.

The primary liability of content-sharing platforms

Article 17 creates a primary liability for online content-sharing service providers giving public access to copyright-protected works uploaded by their users. This is about Youtube or Youtube-like companies. Primary liability means that the platform is liable ipso facto when the illicit content is uploaded, because of the simple act by a third person (the platform user and uploader). It is a very burdensome liability operating ex ante, similar to the ones the civil law provides for very dangerous activities. To better explains this legislative innovation, please note that the current liability regime (in force since 2001 with Directive 2000/31) operates ex post, i.e. via the removal of the illicit content after the uploading. There is a huge difference between a) imposing a system preventing the upload of content ex ante, on one side; and b) providing an ex post removal regime, on the other; and legal implications are very different. If you catch this difference, you are looking at the core of the Copyright debate. All the rest is fresh water 🙂

As a consequence of the above “ipso facto” primary liability, content-sharing platforms must be authorized to have their content uploaded and made available on their website. If not, they are liable and should pay damages. But how can you be authorized even before users decide to upload a given video or music? You should foresee the future. This mechanism seems contrary to common sense and in fact it is.

How could content sharing platforms avoid primary liability?

Still, art. 17 provides that Youtube & CO. can avoid liability thanks to the so-called “mitigation measures”, consisting in demonstrating that they;

(a) made best efforts to obtain an authorisation, and

(b) made, in accordance with high industry standards of professional diligence, best efforts to ensure the unavailability of specific works and other subject matter for which the rightholders have provided the service providers with the relevant and necessary information; and in any event

(c) acted expeditiously, upon receiving a sufficiently substantiated notice from the rightholders, to disable access to, or to remove from, their websites the notified works or other subject matter, and made best efforts to prevent theirfuture uploads in accordance with point (b).

Filter or not filter?

Point b) is obscure. What does it mean “best efforts to ensure the unavailability of content on the platforms”? Does this provision imply mandatory upload filters or not? This is a tricky. The new Copyright Directive never explicitly mentions filters and its supporters, both stakeholders and persons of the European institutions, have been vocal in declaring that upload-filters are not foreseen by the provision. See for instance rapporteur Axel Voss:

Sometimes

Sometimes

However, the sole available technological instrument that a platform can use to effectively avoid primary liability, that is to say to anticipate and prevent a user from uploading and making public illicit content, is a un automated upload-filter. Only filters can enable platforms to identify and block posting and -reposting of illicit content, before they become public. No other technological instruments are available, since non-automated instruments, such as for instance a human check, would be unfeasible. Therefore, only two options are possible:

a) either we accept, even obtorto collo, that only (automated) upload filters may preventively and effectively block illicit content, so that to give a sense, although controversial, to this Copyright Directive; or

b) we could be satisfied with any solutions other than automated upload filters. But this means that such solution could operate only ex post, after illicit content is uploaded and made public (similarly to the current liability regime). Tertium non datur.

Why this Directive pushes towards filtering, but with vague and imprecise terms?

Omitting the term “uploadfilter” in the Directive was a clear and intentional political decision, necessary to facilitate the approval, this is why the supporters of the Directive have been denying that the same is mandating or implying upload filters. At the same time, the Directive itself requires platforms to make make “best efforts” to block illicit content, an objective which could be realistically achieved only by applying upload filters. In practice, the Directive aims at something specific which, however, cannot be said and written down. In the best scenario, it looks like the directive was written down by rabbits, not persons. In the worst scenario, it looks like an imbroglio.

National authorities to decide about filtering?

Since art. 17 is so vague, it will be a matter of national implementation and interpretation by national authorities. When looking at practical cases, national authorities will be able to take various directions but, at the end, only the same 2 options are available: either mandating upload filters, as the only effective instruments to prevent ex ante illicit content to be uploaded on platforms; or any other solutions which, however, will basically work on a ex-post control basis.

What about voluntarily filtering? This could be a possible solution but, as far as filters are not mandatory, they could be replaced by “best efforts” ex-post mechanisms. And, as we know, filters are a big investments that only big companies like BigG can afford. “Simple” filters could be found in the market but would be ineffective and overblocking, with the risk to kill the business.

What are national authorities expected to do in practice? If they look at the text of article 17, imposing an express upload-filters provision will not be obvious, also considering that the Directive contains another contradicting obligation (art. 17(8)): “The application of this Article shall not lead to any general monitoring obligation“.

Rights-holders will probably complain because they pretend unauthorised content to be effectively blocked ex ante, but then they also should explain why upload filters were not required before voting of the directive, while after the approval they are.

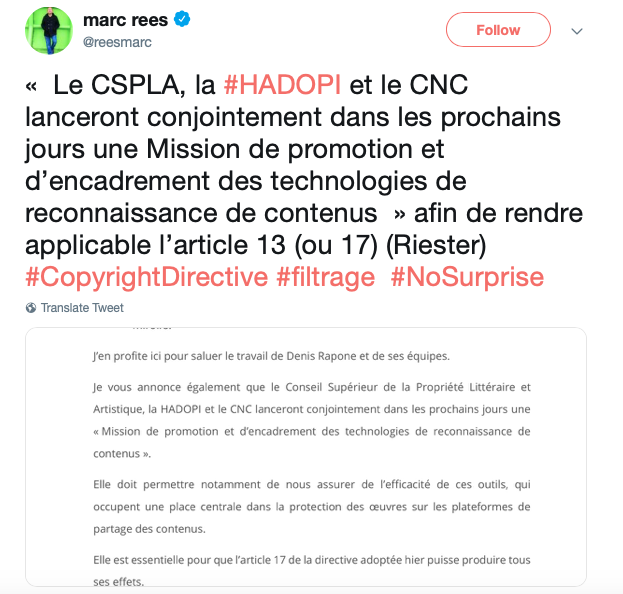

Anyway, there might be national governments which already have clear ideas. The French government, for example, just the day after the approval of the Directive officially stated that they are going to adopt upload filers because they are the only way to make art. 17 working:

Will the Commission recommend filtering?

Unless you are French, it will be difficult for national authorities to take a straight decision on the topic. It is more likely that vagueness and contradictions of the Directive will be transposed into national law, without solving the problem which, therefore, will have to be dealt on the ground: at the very hand, a national judge will have to take the decision on the basis of vague provisions and therefore jurisprudence could strongly differ from country to country. A preliminary ruling to the European court of justice could also be possible.

In the meanwhile, the European Commission will be required to provide guidance on the matter after having heard the views of all concerned stakeholders (platforms, rights holders, users, ecc.) gathering together (art. 17(10)). It is unlikely that such stakeholders will magically find a an agreement on the filters subject, therefore at the very end the Commission will remain holding the bag and will have to decide what to do, what to recommend. Remarkably, the entire system seems designed to postpone, as longest as possible, any decision.

Worth-noting, next European Parliament and Commissioners may be a bit colder vis-à-vis copyright supporters. Therefore, will next Commission recommend national authorities to mandate upload filters or could, instead, recommend a more soft interpretation? This could probably become a question that the new European Parliament will ask to the next candidate commissioner for the Digital Agenda, in July 2019.

Categories: Copyright and Internet